Ivan Djuric, the programme director of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights’ branch in Serbia, told BIRN in an interview that the organisation’s nomination for the Vaclav Havel Human Rights Prize is a recognition that anti-war campaigning remains necessary in the Balkan region.

“When we talk about human rights, we are referring to the Council of Europe, to the European Convention on Human Rights or to the European Court [of Human Rights]; we see them as the last bastion for the defence of our rights, and to be recognized by them means a lot to us. It means that Europe understands why it is important that we are dealing with the prevention of war here today,” said Djuric.

“We feel that this is recognition for our work as an organisation, but also for our ideas and the values we stand for,” he added.

The annual Vaclav Havel Prize, named after the celebrated Czech dissident and statesman, is awarded by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, in partnership with the Vaclav Havel Library and the Charter 77 Foundation, and honours outstanding civil-society activism in defence of human rights.

This year’s shortlisted nominees are an imprisoned Uighur writer in China, Ilham Tohti, a human rights lawyer in Tajikistan, Buzurgmehr Yorov, and the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, which is a network of NGOs operating in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia.

The YIHR was founded in 2003 to campaign for justice, equality, freedom, democracy and peace, and to build cooperation between young activists from the various countries of the Balkans amid the continuing divisions caused by the 1990s wars.

One of the YIHR’s key issues in Serbia is promoting LGBT rights, and it is among the organisers of the annual Belgrade Pride event. In its early years, the Pride march was violently disrupted by right-wing extremists and then banned for three consecutive years due to security concerns, but since 2014 it has gone ahead without any major incident in a cordoned-off area of the city centre under heavy police protection.

Ahead of the next Belgrade Pride on Sunday, September 15, the organisers staged small spin-off events to take the message of tolerance from the capital to smaller Serbian towns and cities.

“We visited ten cities and in most of them, the atmosphere was great, it was well-received,” Djuric said.

He argued that if Belgrade Pride has now become “normalised”, it was the organisers’ responsibility to “share it” by extending Pride Week events to other places across the country.

LGBT activists with placards walked through the centres of eight provincial towns successfully, but in Valjevo and Novi Pazar, the events were cancelled after threats from right-wing groups.

War criminals ‘glorified’

Besides Pride, the YIHR is mostly known in Serbia for its activism around the issue of war crimes, staging interventions that highlight the need to respect court-established facts about the 1990s wars and condemn the perpetrators.

This remains a controversial issue in Serbia, where war crimes committed by Serbs are often denied or played down by the authorities and a convicted war criminal even sits as an MP in parliament – Serbian Radical Party leader Vojislav Seselj.

“I think that moral condemnation [of war crimes] has never really existed here in our society,” Djuric said.

“When we talk about the legal aspects, about war crimes trials and their outcomes, they have always been received poorly here,” he continued. “But I think we are at the lowest point now, because there is no moral condemnation [of convicted war criminals]; on the contrary, the current political elite is literally glorifying them, celebrating state holidays with them, publishing their books,” he explained.

Last year, a Serbian court upheld convictions and fines handed down to eight YIHR activists for disrupting a speech by convicted war criminal Veselin Sljivancanin at an event organised by the ruling Serbian Progressive Party in the town of Beska.

Sljivancanin served a jail sentence for war crimes after being convicted of aiding and abetting the torture of non-Serb prisoners from Vukovar in Croatia in 1991. Since his release, Sljivancanin has been a frequent guest at events organised by the Progressive Party.

Djuric said that this apparent lack of progress in Serbian society can sometimes be frustrating.

“But on the vast majority of days, the feeling is different. You can see a bit of success, that there is something that’s annoying them [deniers of war crimes], that there is that foot in the door. I like to think that we, all of us anti-war activists, have put a foot in the door and that without us, without the whole anti-war movement, that door towards what we call the West, which respects peace, democracy and freedom, would have been closed a long time ago,” he argued.

‘Guardians of memory’

The YIHR in Serbia is involved in organising events like the annual ‘Miredita, Dobar Dan’ festival in the Serbian capital, which showcases Kosovo arts and culture to a Belgrade audience and is intended to bring Serbs and Kosovo Albanians closer together.

It is also involved in the annual commemorations in Belgrade for the victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacres by Bosnian Serb forces, which Serbia refuses to accept constituted genocide despite verdicts from international courts.

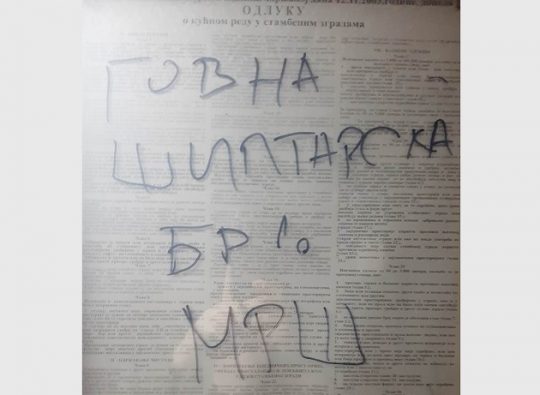

These interventions have provoked strong reactions from nationalists and right-wingers in Serbia, who have issued threats and occasionally tried to violently disrupt events promoting reconciliation between Serbs and Kosovo Albanians.

Djuric argued that activists’ responsibility to truth and justice was more important than any fear of attack.

“For example, if you carry a banner with the names of [Kosovo war] victims buried in a mass grave in Batajnica [near Belgrade], and someone comes up threatening to hit you with a bottle or something, it is dishonourable [to the victims] to be scared. We also have great confidence in the police, because we have seen them doing their job professionally many times,” he explained.

“But I have to say there is also something about the fact that we are trying to be guardians of memory, or protectors of people who suffered much more that we can imagine, so your conscience does not allow you to let the fear out,” he added.